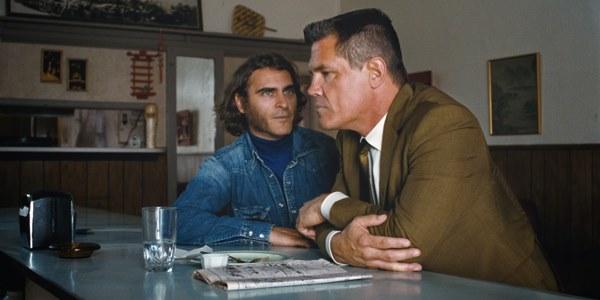

‘You smell like a patchouli fart’, says homicide cop ‘Bigfoot’ (Josh Brolin). His crewcut and skinny black tie signal him to be part of the straight-laced, conservative contingent of his 1970s Los Angeles, antitype to the private investigator he is addressing: mutton-chopped, barefoot ‘Doc’ Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix). Doc is the protagonist in this whimsical spin on the noir detective story, which consistently feels like an off-beat, smoke-wreathed reheat of Chinatown.

The setup is classic noir. Scene one: enter the femme fatale, Doc’s ex-lover Shasta (Katherine Waterston), who asks for his help to sort out a complicated affair involving a shady land development deal, an infamous millionaire and his marital infidelity. Doc takes on the job and soon finds himself mixed up in a murder case. Shasta disappears and the rising action, with its ramifying leads and mounting assemblage of suspicious personages, should be convoluted enough to satisfy devotees of the genre. The non-specialist viewer, however, may walk away wondering what sets the film apart from the pack, and it is a legitimate concern.

Noir crime fiction, often designated ‘hardboiled’ in the US, tends to feature a cynical, hard-drinking antihero who is more or less burnt out by immersion in the underworld dealings of black markets, professional criminals and corrupt police. The hero of Inherent Vice can also be described as burnt out, but in another sense entirely: the alcoholism that almost defines classics of the genre is replaced here by experimental drug use. There is scarcely a scene in which Doc is not inhaling or snorting something. This might primarily be a mechanism for translating into another era the conventions of a genre born out of American Prohibition, but it is so pervasive and consequence-free that it comes perilously close to advertising.

This is ironic, given that one of the subplots of the film involves heroin importers who have also started a line of rehab facilities. They get their customers coming and going. ‘As long as American life is still something to escape from,’ we hear, ‘the cartel will have a deep pool of customers’. However insidious, this is one of the few really clever ideas in a script that is surprisingly unsurprising, given that it is the first work by notoriously ornate literary novelist Thomas Pynchon to be adapted to the screen.

The best thing about the film is probably its whimsy. Doc divertingly reverts to the foetal position, for instance, when Bigfoot tries to arrest him; the latter absurdly grapples with sheer awkwardness of lifting him off the ground, much to our delight. Reactions will be less favourable, though, when this light attitude transfers to the depiction of women, first in the form of revealing miniskirts and casual sexual favours, but culminating in an ugly scene of assault which fixes on the face of the female victim. It might be argued that such misogyny is historically accurate as an underlying feature of the 1970s, yet in the same breath it can be pointed out that the feature films of the era exercised a higher level of discretion when choosing what to show on the screen.

Overall, this is not a motion picture destined to win a wide audience. It may gain cult followers among hardboiled, Pynchon and patchouli diehards, and perhaps even among a wider base of viewers itching for spectacles of airbrushed corruption. Vending this last, Inherent Vice offers a fix but no solution if American life is, indeed, felt as something to escape from. Those persons will probably be most pleased with the two and a half hour odyssey who come to it only expecting to spend that time in the company of LA’s fallen angels.

(Originally published in Thinking Faith)