With its gripping visual style and unembarrassed use of religiously charged symbolism, the 1927 classic Metropolis is one of the first feature length science fiction movies as well as one of the most enjoyable silent movies on the Vatican’s list of notable films.

The story follows Freder, the pampered son of the industrialist overseer of a futuristic dystopia, whom we meet enjoying a dissipated existence atop one of the city’s many skyscrapers.

One day his life changes, though, when a simply dressed young woman surrounded by a swarm of untidy children arrives uninvited from the working class underworld. She bids Freder gaze upon these underprivileged kids, whom she names his unrecognized brothers, and, cut to the heart, Freder spontaneously abandons his pleasure nest, descends to the nether reaches of the city, and throws in his lot with his father’s workers.

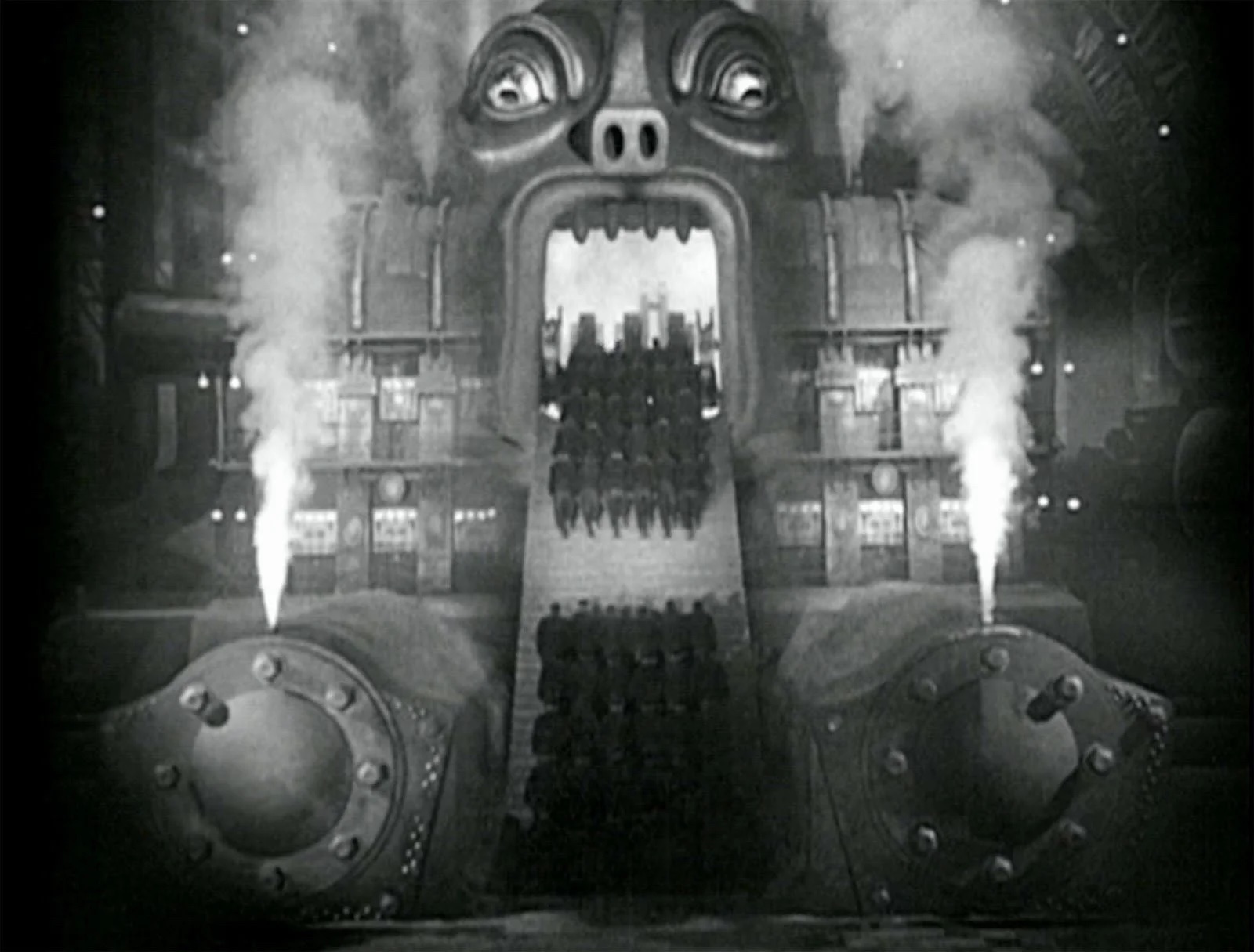

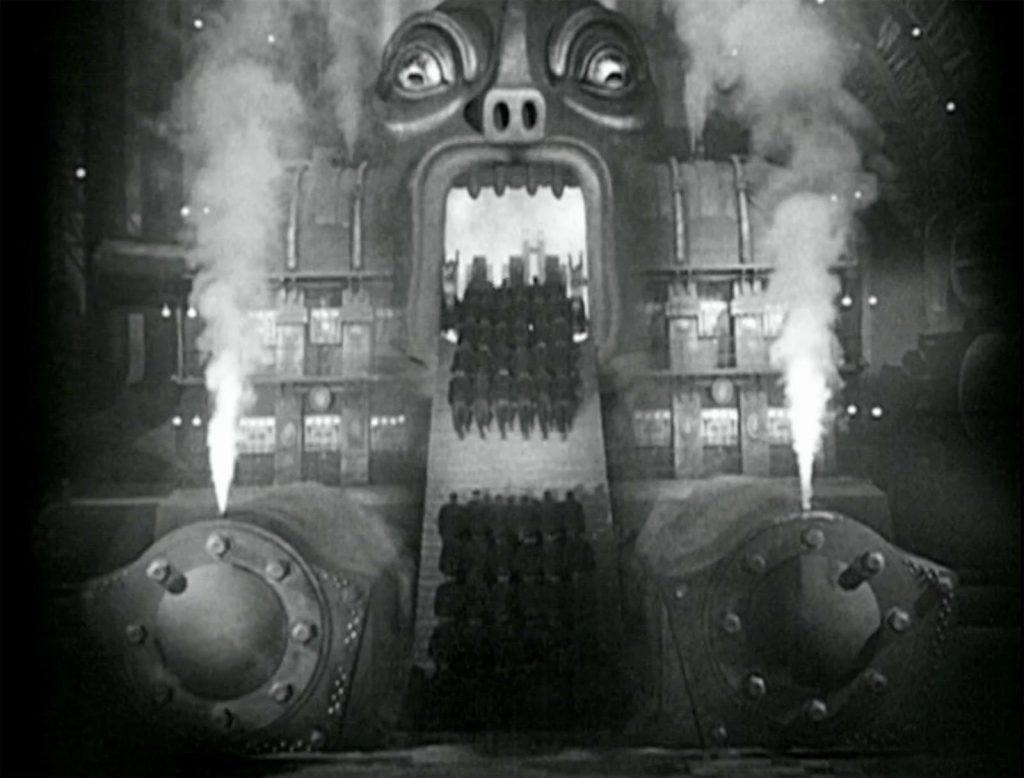

Shortly upon his arrival into the subterranean realm of servile labor, Freder witnesses a giant machine overheat with fatal consequences for many of its operators. Transformed by his overheated imagination into the image of a gargantuan idol called Moloch (so called after one of the pagan gods mentioned in the Old Testament), Freder watches in horror as row after row of men march into its gaping mouth to their destruction like so much raw material processed by an infernal assembly line.

After failing to goad his father into any sort of system-wide reformatory action, Freder swaps places with a factory worker whose physically gruelling task involves manipulating the twin arms of a device that resembles a man-sized clock face. Ground down by the inhumane monotony of the work, there comes a moment deep into his shift when, his hands still gripping the horizontal arms of the clock face, Freder exclaims, “Father! Father! Will ten hours never end??!!”

A deliberate visual and vocal evocation of the Crucifixion, Freder’s posture mirrors Our Lord’s on the Cross, while the syntax of his plea echoes the cry of dereliction recorded in the Gospels, Eloi! Eloi! Lama sabachthani!

Such a deliberate parallel between the hero of this story and the savior of mankind, both of whom voluntarily descend from an empyrion of blissful living into a troubled human world of toil and exploitation, draws special attention to the solidarity the God of Christians enjoys with the poor in this world.

Indeed, in Metropolis Freder is explicitly identified with “the mediator” to whom the weary workers look forward as the one who will someday deliver them from their squalid living conditions.

When after their shift Freder accompanies the exhausted workers into catacombs located even deeper than their underground factory world, they attend a kind of church service reminiscent of some of the most ancient liturgies of the church in Rome (where, especially in times of persecution, Christians would celebrate in secret over the tombs of those who had recently been killed for the faith).

Backed by a candlelit altar and numerous crosses, the same the simply dressed young woman, who earlier brought the message of fraternal solidarity to Freder and whose name we now discover is Maria, delivers a kind of sermon on what she calls the “legend” of the Tower of Babel (which, incidentally, is the same name given in the film to the glistening edifice which serves as Freder’s father’s industrial headquarters).

On her telling, this biblical episode is rendered a cautionary tale about class conflict, with the tower itself depicted as coming together only through the straining labor of hoards of half-clothed workers. Contrasted with the robed and leisured elites who designed and commissioned the tower, the crowd of laborers storms the half-finished building and razes it to its blood soaked foundations.

“The hands that built the Tower of Babel knew nothing of the dream of the brain that had conceived it,” Maria relates, “People spoke the same language, but could no longer understand each other.” She concludes her homily with the utterance that also serves as the film’s opening and closing epigraph, “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart!”

These are only some of the suggestive angles on religious themes advanced by the film, which if nothing else, offers up out of the past a refreshing dose of substantial reflection sadly missing from many of the cinematic options at the moment.

(Content advisory: this film includes a few scenes of partial nudity.)