An introverted adventure through the consciousness of a woman ambiguously represented as either schizophrenic or a modern day shaman, the first season of the Amazon Original series Undone offers a journey that, stimulating while it lasts, fails to wind up anywhere very particular.

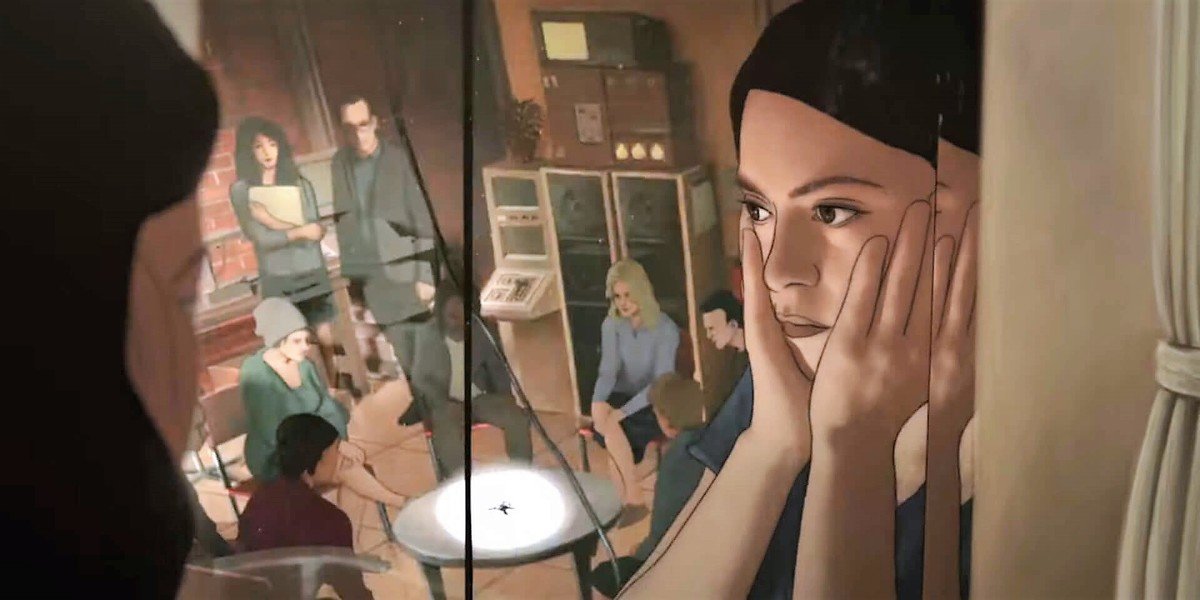

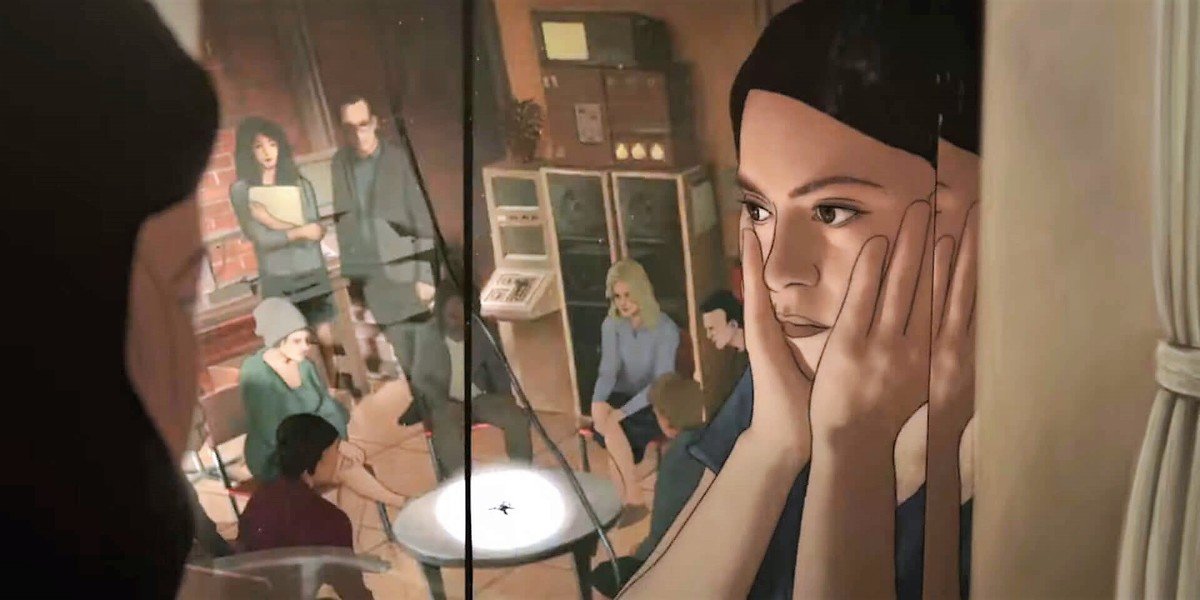

Animated in the hybrid style named after an outdated technology, rotoscoping, the beguiling fusion of the animation-over-live-action is one of the principal interests of these episodes. As protagonist Alma searches her memories (or is it travels back in time) for clues about her father’s death, the relatively uncommon cinematic technique proves particularly appropriate.

The stepped-up suspension of disbelief that all animation demands makes pretty plausible, for example, such mind-bendy phenomena as Alma manipulating the sequence of time at will, conversing with deceased relatives, and running down a hallway only to interact with her past self.

The scattered, non-linear storytelling that results offers a refreshing change of pace from more standard cookie-cutter fare. And the series might also provide some sympathetic insights into some persons’ struggles over mental health.

The flipside of these strengths is the series’ primary weakness, however. What works well as a dazzlingly conceived, pseudo-metaphysical thought piece in speculative psychology proves in the end to be relatively superficial as a story about recognizable humanity.

To put it another way, the interest of Undone lies almost entirely at the surface. And while there is much to like at that level – genuinely amusing characters, innovative visuals, the conspicuously unconventional story structure – all of this overdriving intellect does not manage in the end to elicit more than fleeting feelings of affection.

We like what’s happening while it’s happening, and pretty much forget it as soon as it’s done.

The problem, I think, comes down to a misplaced emphasis that might even amount to a misguided principle. It can perhaps be articulated thus: deep down we are all really different.

Let there be no mistake: up to a certain point, individuality is certainly real. I am me and you are you and Aunt Bertha is her, thanks be to God. Each of us is a unique subsistence, a philosopher might say, unrepeatably crafted and personally sustained by the love of God.

At the same time, what the medievals said of the angels is not the case for us. Each of us is not a unique substance, that is, the lone specimen in his or her own species.

In other words, deep down, no matter our differences, we share something in common and can therefore be called by a common name, i.e. human.

What Undone seems to miss at times in its sometimes rather stringent critique of neuronormativity is the commonality at the back of our diversity.

By insisting all but exclusively upon difference, the series loses touch with what makes such difference delightful, namely, a sense of how we are the same “even so.”

Such misplaced emphasis upon uniqueness might be called one of the weaknesses of contemporary identity politics in general. Declaring, rightly, that every individual is ultimately unlike every other, various lopsided advocacies too quickly absolutize this difference and conflate it with observable qualities like gender, sexuality, race, and, in the present case, cognitive function.

The result, paradoxically, is the institution of diverse identities with which others cannot identify. I can recognize you as different, but our joy (like our skin colour) will never be the same.

A perspective more consistent with the principles of Christianity, I suggest, acknowledges real sharing in the midst of real difference. Ultimately, Christians believe, the truth of any individual thing can only be found in that mystery of unity in diversity which is the Trinitarian ground of all reality.

Communion, in other words, presupposes both difference (com- or “withness”) and union.

However often along the way in the wild ride of life we might pass one another like ships in the night, the community of faith can always rejoice as one in our origin and end.

(Originally published in The B.C. Catholic)